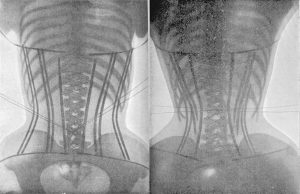

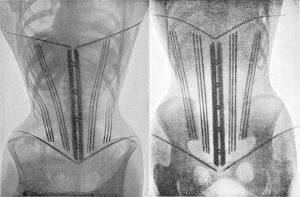

In 1908, a doctor used X-rays to highlight the damaging effects of tight corsets on a woman’s body.

For centuries, boned bodices formed part of a lady’s everyday wardrobe, but it wasn’t until the invention and implementation of the metal eyelet — the holes through which the laces were threaded — in the 1820s and 30s that something called tight lacing came into effect.

This is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: pulling and tying the laces of a corset tight to give the wearer a desired shape; generally along the lines of an hourglass, with a tightly pulled-in waist.

This caused, of course, the familiar fainting to which fashionable young ladies were prone; they were often laced so tightly that they could barely breathe; to help her recover, those around her would loosen her stays (the laces), allowing air to flood back into her constricted lungs.

This, however, was merely the most obvious of the health problems associated with tight lacing, and the garment was the subject of hot debate between those who believed the corset beneficial (mostly the women who actually wore corsets), and those who believed it injurious to the health of the wearer. Indeed, The Lancet, one of the world’s oldest medical journals, published two articles on the subject — one on June 14, 1890, entitled Death From Tight Lacing and the second on January 16, 1892, called Effects of Tight Lacing.

Neither was particularly approving of the practice. The former stated that its consequences “cannot be but hurtful.” It went on, “the veriest novice in anatomy understands how by this process almost every important organ is subjected to cramping pressure, its functions interfered with, and its relations to other structures so altered as to render it, even if it were itself competent, a positive source of danger to them. ”

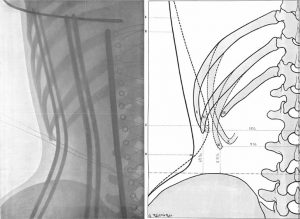

Indeed, the medical community fairly roundly condemned tight lacing. Surgeon William Henry Flower included it as a deforming fashion in his book Fashion in Deformity, an 85-page volume that included skull-shaping, foot-binding and tooth-filing among its subjects, along with an illustration of its effect on the rib cage. Tight lacing over a long period of time does cause the size of the wearer’s waist to shrink as the internal structure of the body shifts to accommodate the constriction.

The effect of tight restriction on the lungs was particularly troubling; the lower lobes of the lungs are prevented from expanded fully when taking a breath, resulting in extra strain. This exacerbated lung conditions such as tuberculosis and pneumonia, which effect the lower lungs first, making the condition much more serious — and both illnesses were much more prevalent before the invention of vaccines in the 20th century.

The other serious problem caused by tight lacing over an extended period of time is atrophy of the back muscles and pectoral muscles, as the corset’s boning does the work of keeping the wearer’s back straight — which, in turn, leads to greater reliance on the corset.

Overall, there seems to be little direct evidence that tight lacing had permanent effects on the wearer. Nevertheless, the restriction of the organs — which could cause poor digestion, poor breathing and poor function otherwise while wearing a tightly laced corset — was a cause for concern for some doctors.

One such was Ludovic O’Followell, a French doctor who in 1905 and 1908 published books on the effects of the corset on female health. O’Followell, however, had something that all the previous arguments and illustrations did not: he used a brand new technology to bolster his arguments.

X-ray had been discovered in just 1895 — a breakthrough that netted Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen the very first Nobel Prize in Physics. The unknown radiation, he noticed, passed through human tissue, but not human bone; it was in diagnostic use just a year later in 1896.

It was this that O’Followell used to illustrate the effects of tight lacing on the ribcage, in a series of striking images included in a paper entitled Le Corset. In it, he argued that the corset not only affected a woman’s physical health, but also her behaviour. He cites novelist Arabella Kenealy, who in 1904 penned an article about the ill effects of the corset — including an account of a strange and possibly nonexistent experiment involving putting corsets on monkeys — noting that she blamed the corset for “bad language.”

However, although the corset was to fall out of fashion in the 1920s, when flapper dresses introduced a more androgynous shape in rebellious response to tight lacing, O’Followell’s intention was not to abolish the corset altogether; instead, he hoped merely to encourage the development of a more healthy and comfortable corset.

You can find the full text of O’Followell’s treatise here (translated from the French), and the full collection of illustrations and photographs here (contains some images that are NSFW).